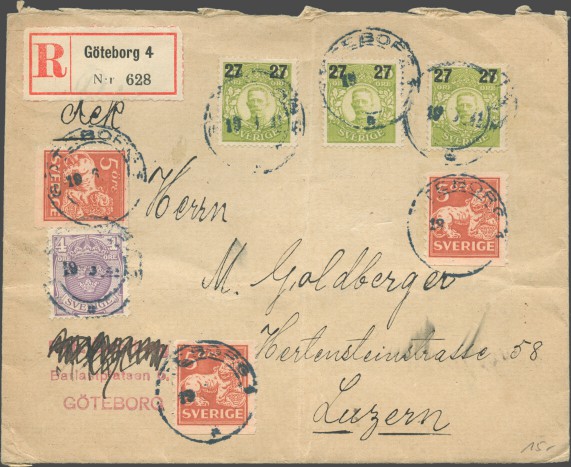

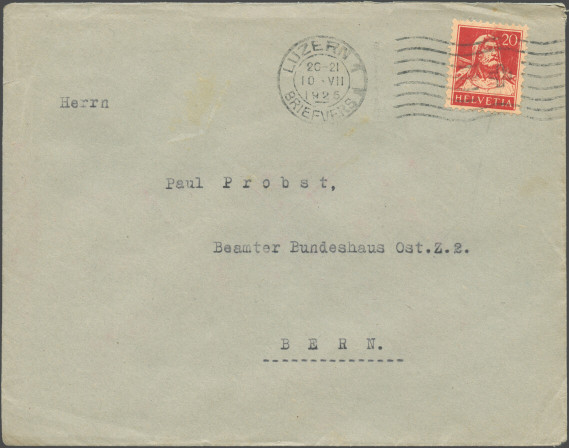

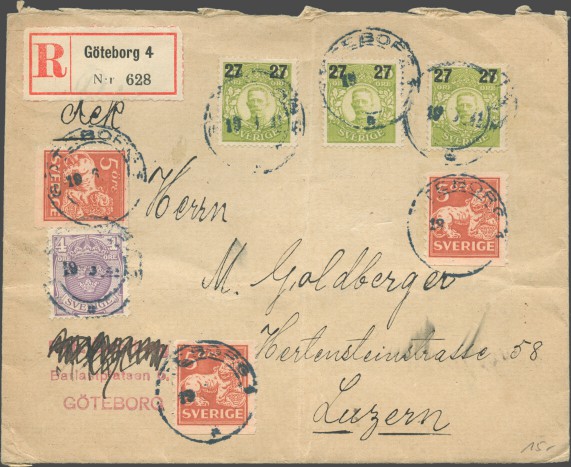

Cover — 1921 – 1923

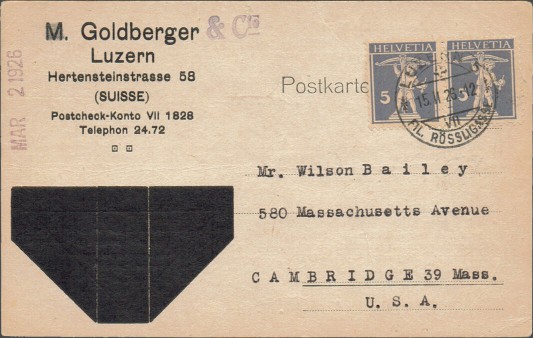

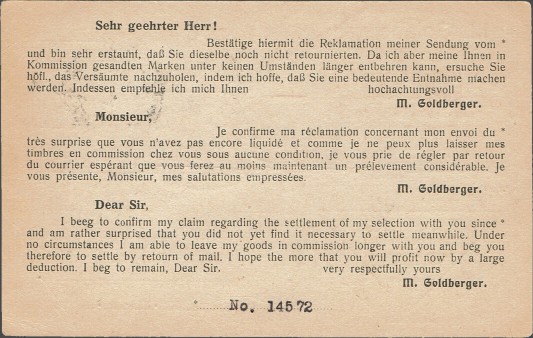

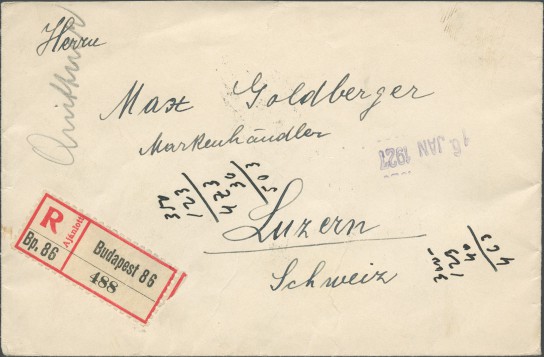

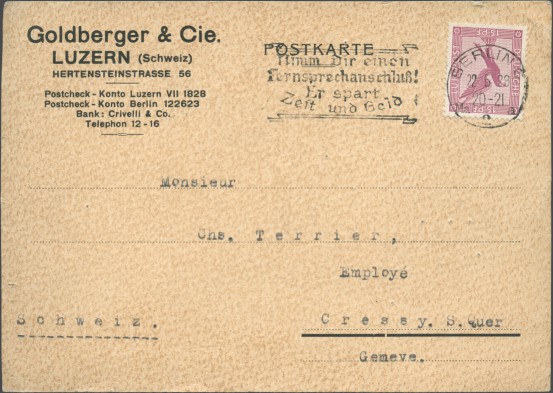

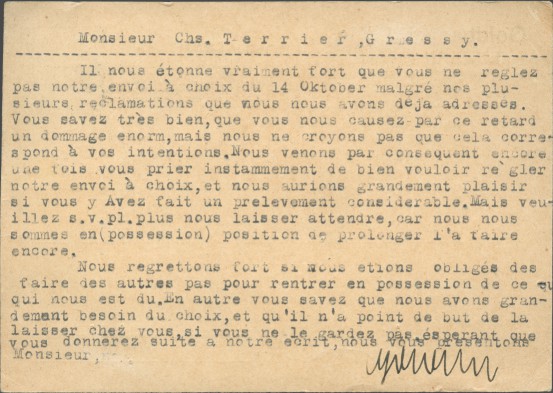

Prokura). In October 1920, while still working for Béla, he opened his own stamp business

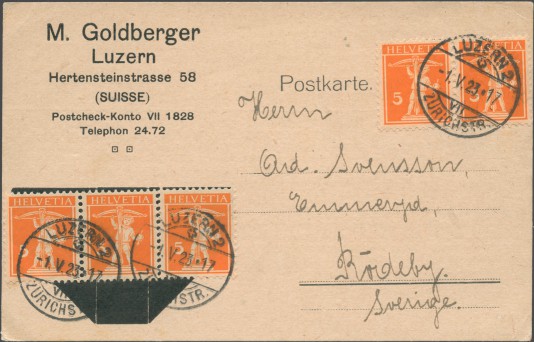

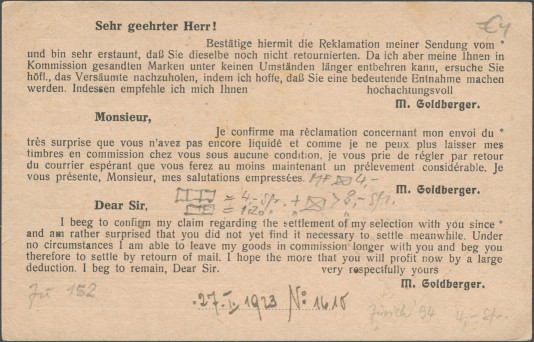

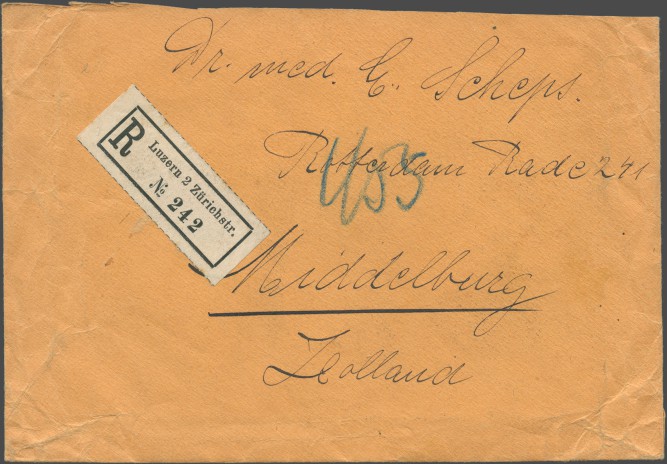

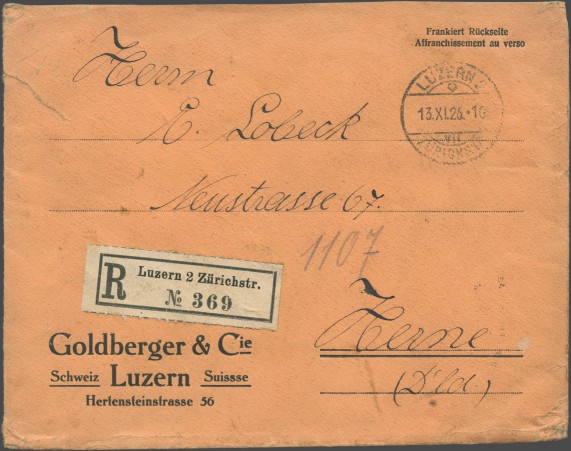

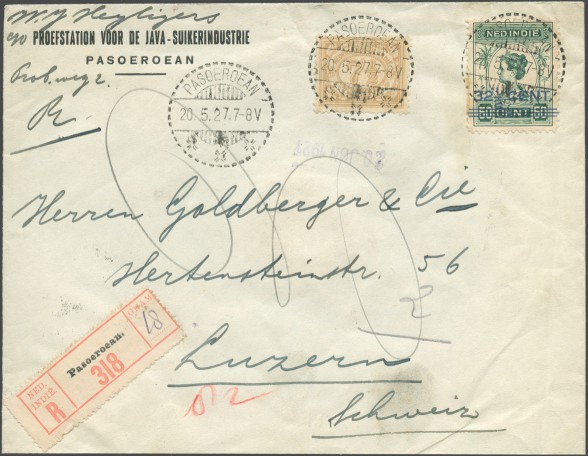

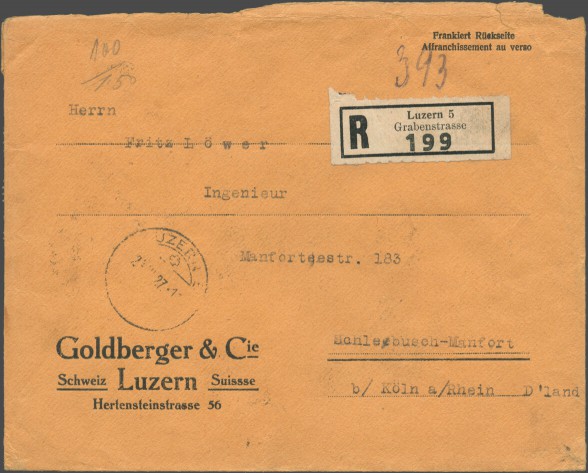

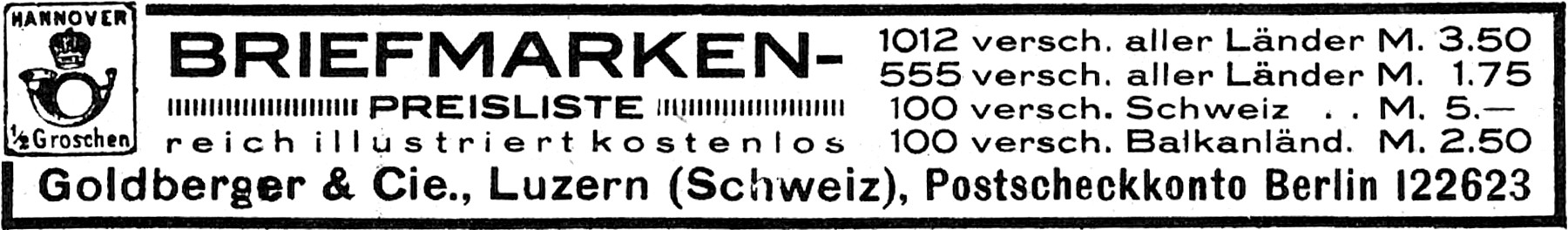

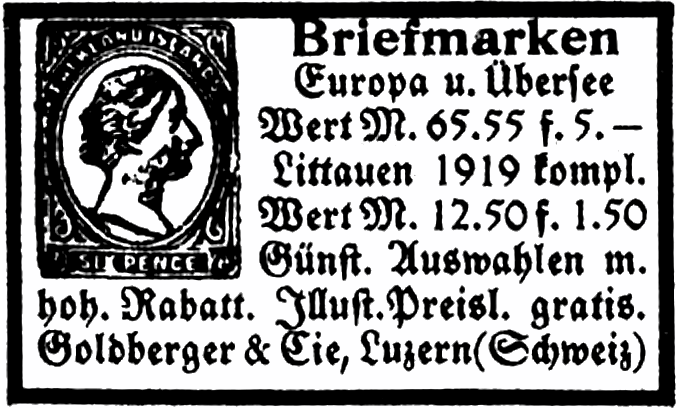

Max Goldbergerin Lucerne at Hertensteinstr. 58. In February 1922, Max Goldberger’s Prokura at Béla’s company expired. In June 1923, Goldberger’s stamp business was transformed into

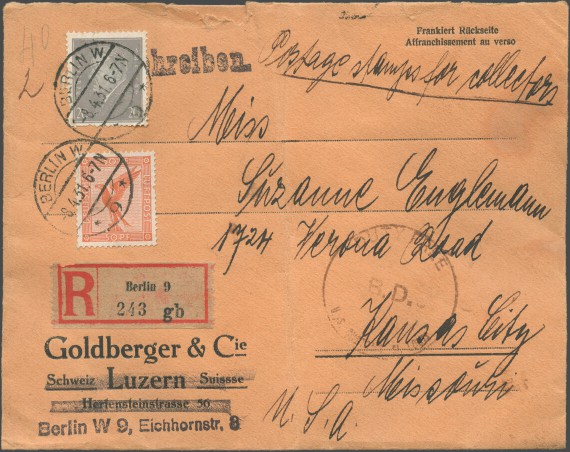

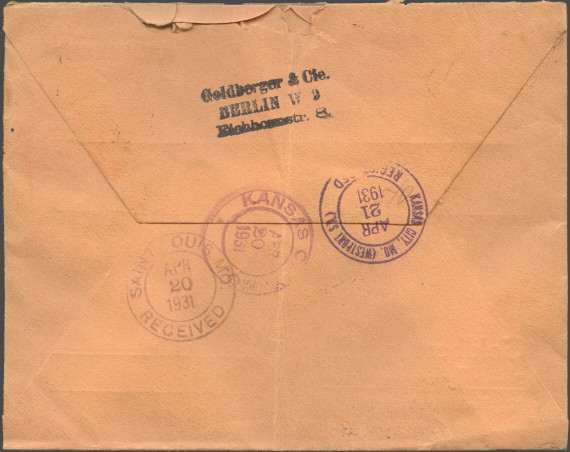

Max Goldberger & Cie, with him and his wife as owners. In July 1929 their company was deleted from the Swiss company register when the Goldberger family left Switzerland to reopen their stamp business at Eichhornstr. 8 in Berlin. Two years later the Goldbergers made it into the news: In late 1931, after selling new prints of rare stamps as originals Max Goldberger and his son Ladislav were sentenced to three and six months in prison, respectively, for fraud. In 1934 Goldberger & Cie moved to Friedrichstr. 160. Max Goldberger died on August 5, 1936 at age 61 in Berlin.

After his father’s death Ladislav Goldberger left Germany and moved to Paris. There he continued to try his hand at the stamp trade, but after the outbreak of the war this became increasingly difficult and he began to struggle financially. In addition, after the German invasion in June 1940, things became less and less safe for him. In the spring of 1943, the Swiss consul in Paris organized transport for Swiss Jews back home. However, despite the circumstances Ladislav decided against returning to Switzerland and even confirmed with his signature that he wished to remain in Paris at his own risk. In December 1943 he was arrested by the Gestapo and interned in Drancy. Unlike other Swiss Jews interened there who were later handed over to the Swiss consul, the Swiss citizenship of the Hungarian native Ladislav was ignored by the German side. On January 20, 1944, he was deported to the Extermination Camp in Auschwitz Birkenau, Poland, where he died in the Holocaust.